In late 2023, a group of experts and government leaders met in Addis Ababa to discuss land policy in Africa in light of the African Continental Free Trade (AfCFTA) agreement.[1] This agreement – from which State Parties expect nothing short of a miracle – aims to promote trade and investment between African countries. Given that land is central to the economic, social and cultural life of every country in the region, and with land conflicts rife, it is clear that access to land will be key to those wishing to “take advantage” of the AfCFTA. Africa is increasingly a target for land grabbing by agrobusiness, elites and those wanting to cash in on “carbon credits”. A major issue is on the table. What impacts will the AfCFTA have on land and what are the risks for local communities that depend on it?

These questions are all the more pressing since, just a few months earlier, in February 2023, the member states of the AfCFTA adopted a specific protocol on “investment”[2]. As in any free trade agreement, this protocol sets out the standards that every country must implement to stimulate investment and protect investors across the contracting parties. But unlike other trade deals, the AfCFTA protocol specificically mentions the land rights of local communities.

Given that the AfCFTA could lead to a rise in demand for African land from agricultural and other investors, and that climate policies are increasingly looking to land projects to “capture” carbon, the risks for local communities whose livelihoods rely on land will be great.

What does this protocol say, exactly? Who will it benefit? How should we deal with it?

The protocol and land: a springboard to privatisation?

The AfCFTA Protocol on Investment aims to encourage intra-African investment flows. It will replace all existing investment agreements between African countries and become the African policy framework on the issue. It will be implemented according to national legislation, which means that the protocol is not directly applicable; instead, it will have to be transposed into national law, which will then shape its impact. As such, protected investments will be permitted in accordance with the national legislation in each host country.

The principles of the protocol are the same as those found in any similar agreement. Investors from State Parties must be given equal treatment to national investors, and their investments cannot be “expropriated” without compensation. The dispute settlement system has not yet been decided upon, but it is highly likely that governments will attempt to avoid the much-criticised Investor-State Dispute Settlement mechanism. Indeed, the protocol features some modern and progressive language, with such issues as gender equality, the existence of indigenous peoples and the importance of local communities mentioned here and there.[3]

The protocol does include several provisions relating to land. First, it gives foreign investors the ability to access land in a member state of the AfCFTA as part of their project. Investment is defined as an “enterprise or company […] which is established, acquired or expanded in conformity with the laws and regulations of a Host State.” Under the protocol, this enterprise may possess assets such as property, licences to cultivate, concessions, liens and other types of contracts. Land is clearly targeted within this, albeit not explicitly, and investor’s land-related rights are to be respected.

The protocol sets out obligations accordingly. Investors are obliged not to exploit or use natural resources in any way that would be detrimental to the rights and interests of the Host State and local communities, to respect the rights and the dignity of indigenous peoples and local communities, as well as “legitimate tenure rights” to land, water, fisheries, and forests.[4]

This progressive-sounding language goes further still. According to the protocol, indigenous peoples and local communities have the right to free, prior and informed consent as well as to participate in the benefits of the investment. Moreover, investors must conduct environmental and social impact assessments, submit them to the competent authorities and make them available and accessible to local communities and indigenous peoples and to any other stakeholder in the territory of the Host State.

The main concern of the experts who went to Addis was how this might be made operational. And herein lies the potential problem. None of these community “rights” will be respected if they are not enshrined in national law, given that the protocol of the AfCFTA does not replace national legislation. In reality, very few land laws in Africa recognise the customary or traditional tenure rights to land, forests or water[5], meaning they would have to be revised.

This is where the experts and policy advisors are looking to intervene: to use the AfCFTA to expedite the establishment of land markets that would serve investors as much as communities. This would likely involve the privatisation of land as long promoted by the World Bank, the African Development Bank and the Economic Commission for Africa. In other words, the protocol may be a springboard to standardise land laws in the name of making the AfCFTA easier to implement. The fear is that this means neoliberal land laws.

Who will benefit from the protocol?

As a whole, over 90% of foreign investment that “enters” African countries – such as plans for a supermarket in Dakar or a palm oil company in Gabon – comes from outside the African continent.[6] The AfCFTA aims to reverse this situation. The protocol itself has been carefully worded to place an emphasis on African investors and stresses that these investors – along with the African states in which investments are made – will be the ones to benefit from it. Therefore, one might expect to see homegrown elites that are driving national agricultural projects in Africa – such as the Kibabki and Kenyatta families in Kenya, Dangote in Nigeria, Baba Danpulo in Cameroon and the Billon family in Côte d’Ivoire – encouraged to further extend their grip.

But, on closer inspection, the protocol does not exclude non-African investors.

In terms of safeguards, it merely insists that all investors must have “substantial business activity” in the territory of a State Party of the AfCFTA in order to benefit from its protection when investing in the territory of another State Party.[7] It is common knowledge that many multinational companies have regional headquarters or subsidiaries in Africa. Equally, investment funds and sovereign funds have a significant legal and economic presence in countries such as South Africa or Mauritius, which offer a highly favourable business climate and tax legislation.

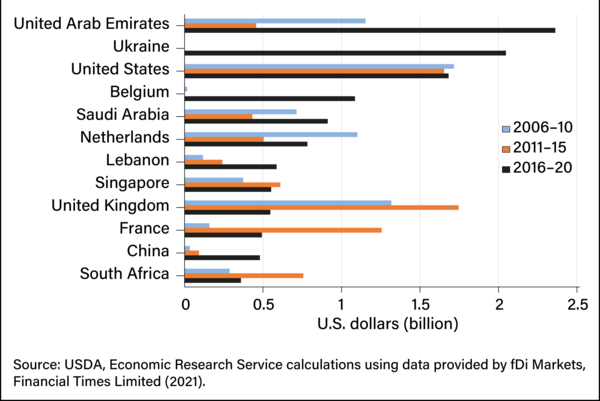

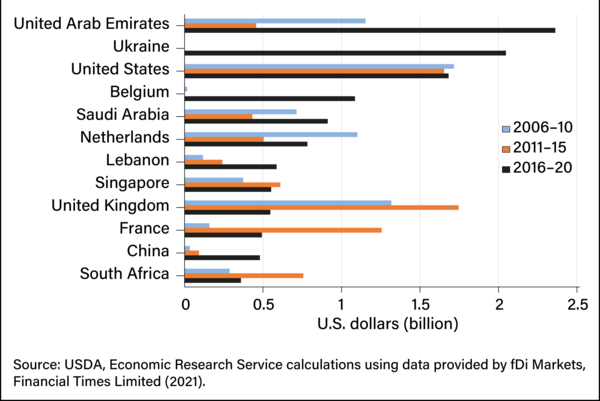

In the agricultural sector, which forms the bedrock of daily life in Africa, this is an important reality. A recent study by the United States government reveals the countries of origin of foreign investors in the African agri-food sector, indicating who might have a stake in how the protocol plays out.[8]

Foreign investment in Africa’s food sector by source country, 2006-2020

We know that many foreign companies and investment funds are looking to develop their business in Africa once the AfCFTA becomes operational. For example, major groups from the United Arab Emirates whose activities centre on farm production and trade are banking heavily on the African market thanks to the AfCFTA.[9] The UAE is the 4th largest source of foreign investment in Africa after China, Europe and the United States, and is counting on the AfCFTA to bolster their presence.[10] One key detail worth mentioning is that Abu Dhabi is in the process of signing a free trade agreement with Mauritius to facilitate economic access and legal stability for Emirati firms throughout sub-Saharan Africa, where Mauritius will serve as a bridgehead.[11] In July 2024, the Director of DP World announced that he would be working with the Secretariat of the AfCFTA to handle logistics for future intra-African trade.[12] All these projects risk destabilising communities’ control over land and their own local food markets.

The same applies for the new “climate” projects currently taking off in Africa.

AfCFTA: will the land market fuel the carbon market?

The AfCFTA protocol specifically champions climate projects at a time when foreign investments for the production and sale of carbon offsets are gaining ground.[13] Some, like the TotalEnergies project in Congo, are already being fought against due to their impacts on the rights of local communities.[14] Others are less prominent, such as the agreements signed by African Agriculture Inc with two municipalities regarding 2.2 million hectares of land in Niger.[15] A recent investigation by GRAIN revealed that large-scale tree and crop planting projects for carbon credits cover over 9.1 million hectares of land in the global South, 5.2 million hectares of which are in Africa.[16] In Côte d’Ivoire, the French company aDryada is rapidly expanding with state support, privatising nearly 70,000 hectares of land for its carbon offsetting.[17] These projects are transferring control over the land from peasant, forest and fishing communities to (largely foreign) investors. The AfCFTA risks supercharging this process.

The risk is very real indeed. A group of researchers who attended the meeting in Addis Ababa stressed that the carbon credit market in Africa serves mainly foreign interests, the same interests that manage the projects and pocket the revenue. They also emphasised the need to solve the problem of collective land rights for local communities in Africa before these investments are made.[18]

Other multinationals that have invested massively in Africa have a different perspective. For example, Socfin – which hold concessions covering 320,000 hectares in Africa for the production of rubber and palm oil – appears concerned about the competition that the AfCFTA could unleash in Nigeria.[19] “If we are unable to manage imports as an ECOWAS country, I find it hard to imagine what will happen when 54 countries begin trading together. As far as we are concerned, it will be a disaster,” declared Graham Hefer, CEO of Okomu Oil Palm Company, Socfin’s most profitable subsidiary in Africa.

What can be done about it?

It is important to be aware that the AfCFTA may pave the way for international firms, as well as certain wealthy countries, to acquire land to the detriment of local communities in Africa. It is true that there is one option in the protocol’s text that could prevent such a situation. On a national level, governments could designate food or agriculture a “critical sector” to which the protocol on investment would not apply. However, given the importance that African governments attach to the role of private investors, it is unrealistic to think that any one of them would exercise this option.

Therefore, it is important to raise awareness of this protocol and debate it, particularly with local communities, who risk losing control of their land, their forests and other resources. Too many of the battles currently being fought in Africa against land grabbing and for climate justice risk being jeopardised by investors who are set to profit from the protocol, all the more so as the agribusiness model itself is central to the agricultural vision of the AfCFTA. We need to promote another path towards a more democratic prosperity, one that is based on popular sovereignty and which respects the rights of local communities.

[3] In the protocol, the recognition of indigenous peoples is entirely dependent on national legislation; indeed. Very few African nations recognise these peoples, let alone their collective land rights. See Article 3.6.

[5] Liberia and Mali are the exceptions. See https://rightsandresources.org/tenure-tracking/

[6] Prachi Agarwal et al, “Exploring data on foreign direct investment to support implementation of the AfCFTA Protocol on Investment”, Overseas Development Institute, 9 September 2024, https://odi.org/en/publications/exploring-data-on-foreign-direct-investment-to-support-implementation-of-the-afcfta-protocol-on-investment/

[7] Article 1, definition of “Investor”.

[8] Michael E. Johnson et al., “Market opportunities expanding for agricultural trade and investment in Africa”, Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, 6 January 2023, https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2023/february/market-opportunities-expanding-for-agricultural-trade-and-investment-in-africa/

[10] Dubai Chamber of Commerce, “AFCFTA could boost Dubai-Africa trade by 10% over next 5 years”, 17 August 2020, https://www.dubaichamber.com/en/media-center/news/afcfta-could-boost-dubai-africa-trade-by-10-over-next-5-years/

[11] Emirates News Agency, “AE ministers, officials emphasise importance of Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement with Mauritius”, 22 July 2024 https://www.wam.ae/en/article/b4ag6p1-uae-ministers-officials-emphasise-importance

[12] Nehal Gautam, “How will AfCFTA transform intra-African trade & overcome regulatory issues?”, Logistics Update, 13 July 2024, https://www.logupdateafrica.com/trade/how-will-afcfta-transform-intra-african-trade-overcome-regulatory-issues-1352649

[13] See Article 26(a) in particular

[14] CCFD, “Total au Congo, une opération de greenwashing destructrice” (EN: “Total in Congo: a destructive greenwashing operation”) updated 25.09.2024, https://ccfd-terresolidaire.org/total-au-congo-une-operation-de-greenwashing-destructrice/

[15] GRAIN, “Purchasing land in Niger for carbon credits: the new form of greenwashing sweeping Africa”, 9 November 2022, https://grain.org/en/article/6909

[16] GRAIN, “From land grabbers to carbon cowboys: a new scramble for community lands takes off”, 25 September 2024, https://grain.org/en/article/7190

[17] Arbaud Deux, “La Côte d’Ivoire se lance dans les crédits carbones pour financer sa reforestation” (EN: “Côte d’Ivoire launches carbon credit scheme to finance reforestation”), Le Monde, 1 May 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2024/05/01/la-cote-d-ivoire-se-lance-dans-les-credits-carbone-pour-financer-sa-reforestation_6230985_3212.html

[18] Dr. Simbarashe Tatsvarei et al., “Large scale land-based carbon credit trading within African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), prospects and potential institutional arrangements”, https://www.conftool.org/africalandconference2023/index.php?page=browseSessions&form_session=243&presentations=show

[19] Figures are as of 31 December 2023. See Socfinaf, “2023 Annual Report”, https://socfin.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2023-Socfinaf-Annual-report.pdf

Original title: “For Africa’s food and beverage sector, the United States consistently has been one of the top sources of greenfield foreign direct investment, 2006-20”; fromMarket Opportunities Expanding for Agricultural Trade and Investment in Africa,U.S. Department of AgricultureWe know that many foreign companies and investment funds are looking to develop their business in Africa once the AfCFTA becomes operational. For example, major groups from the United Arab Emirates whose activities centre on farm production and trade are banking heavily on the African market thanks to the AfCFTA.[9] The UAE is the 4th largest source of foreign investment in Africa after China, Europe and the United States, and is counting on the AfCFTA to bolster their presence.[10] One key detail worth mentioning is that Abu Dhabi is in the process of signing a free trade agreement with Mauritius to facilitate economic access and legal stability for Emirati firms throughout sub-Saharan Africa, where Mauritius will serve as a bridgehead.[11] In July 2024, the Director of DP World announced that he would be working with the Secretariat of the AfCFTA to handle logistics for future intra-African trade.[12] All these projects risk destabilising communities’ control over land and their own local food markets.The same applies for the new “climate” projects currently taking off in Africa.AfCFTA: will the land market fuel the carbon market?The AfCFTA protocol specifically champions climate projects at a time when foreign investments for the production and sale of carbon offsets are gaining ground.[13] Some, like the TotalEnergies project in Congo, are already being fought against due to their impacts on the rights of local communities.[14] Others are less prominent, such as the agreements signed by African Agriculture Inc with two municipalities regarding 2.2 million hectares of land in Niger.[15] A recent investigation by GRAIN revealed that large-scale tree and crop planting projects for carbon credits cover over 9.1 million hectares of land in the global South, 5.2 million hectares of which are in Africa.[16] In Côte d’Ivoire, the French company aDryada is rapidly expanding with state support, privatising nearly 70,000 hectares of land for its carbon offsetting.[17] These projects are transferring control over the land from peasant, forest and fishing communities to (largely foreign) investors. The AfCFTA risks supercharging this process.The risk is very real indeed. A group of researchers who attended the meeting in Addis Ababa stressed that the carbon credit market in Africa serves mainly foreign interests, the same interests that manage the projects and pocket the revenue. They also emphasised the need to solve the problem of collective land rights for local communities in Africa before these investments are made.[18]Other multinationals that have invested massively in Africa have a different perspective. For example, Socfin – which hold concessions covering 320,000 hectares in Africa for the production of rubber and palm oil – appears concerned about the competition that the AfCFTA could unleash in Nigeria.[19] “If we are unable to manage imports as an ECOWAS country, I find it hard to imagine what will happen when 54 countries begin trading together. As far as we are concerned, it will be a disaster,” declared Graham Hefer, CEO of Okomu Oil Palm Company, Socfin’s most profitable subsidiary in Africa.What can be done about it?It is important to be aware that the AfCFTA may pave the way for international firms, as well as certain wealthy countries, to acquire land to the detriment of local communities in Africa. It is true that there is one option in the protocol’s text that could prevent such a situation. On a national level, governments could designate food or agriculture a “critical sector” to which the protocol on investment would not apply. However, given the importance that African governments attach to the role of private investors, it is unrealistic to think that any one of them would exercise this option.Therefore, it is important to raise awareness of this protocol and debate it, particularly with local communities, who risk losing control of their land, their forests and other resources. Too many of the battles currently being fought in Africa against land grabbing and for climate justice risk being jeopardised by investors who are set to profit from the protocol, all the more so as the agribusiness model itself is central to the agricultural vision of the AfCFTA. We need to promote another path towards a more democratic prosperity, one that is based on popular sovereignty and which respects the rights of local communities.[1] Visit the conference website at https://www.uneca.org/eca-events/2023-conference-land-policy-africa for the documents and videos, in English only.[2] Available in English here: https://www.bilaterals.org/IMG/pdf/en_-_afcfta_protocol_on_investment.pdf. The protocol was adopted on 19 February 2023 and will enter into force once it has been ratified by 22 countries. It is therefore currently being ratified on a national level.[3] In the protocol, the recognition of indigenous peoples is entirely dependent on national legislation; indeed. Very few African nations recognise these peoples, let alone their collective land rights. See Article 3.6.[4] Article 35.2.[5] Liberia and Mali are the exceptions. See https://rightsandresources.org/tenure-tracking/[6] Prachi Agarwal et al, “Exploring data on foreign direct investment to support implementation of the AfCFTA Protocol on Investment”, Overseas Development Institute, 9 September 2024, https://odi.org/en/publications/exploring-data-on-foreign-direct-investment-to-support-implementation-of-the-afcfta-protocol-on-investment/[7] Article 1, definition of “Investor”.[8] Michael E. Johnson et al., “Market opportunities expanding for agricultural trade and investment in Africa”, Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, 6 January 2023, https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2023/february/market-opportunities-expanding-for-agricultural-trade-and-investment-in-africa/[9] GRAIN, “From land to logistics: UAE’s growing power in the global food system”, 12 July 2024, https://grain.org/en/article/7170. The Emiratis’ overall interest in the AfCFTA is explained well by Chido Munyati in “A new economic partnership is emerging between Africa and the Gulf states”, World Economic Forum, 28 April 2024: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/04/africa-gcc-gulf-economy-partnership-emerging/[10] Dubai Chamber of Commerce, “AFCFTA could boost Dubai-Africa trade by 10% over next 5 years”, 17 August 2020, https://www.dubaichamber.com/en/media-center/news/afcfta-could-boost-dubai-africa-trade-by-10-over-next-5-years/[11] Emirates News Agency, “AE ministers, officials emphasise importance of Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement with Mauritius”, 22 July 2024 https://www.wam.ae/en/article/b4ag6p1-uae-ministers-officials-emphasise-importance[12] Nehal Gautam, “How will AfCFTA transform intra-African trade & overcome regulatory issues?”, Logistics Update, 13 July 2024, https://www.logupdateafrica.com/trade/how-will-afcfta-transform-intra-african-trade-overcome-regulatory-issues-1352649[13] See Article 26(a) in particular[14] CCFD, “Total au Congo, une opération de greenwashing destructrice” (EN: “Total in Congo: a destructive greenwashing operation”) updated 25.09.2024, https://ccfd-terresolidaire.org/total-au-congo-une-operation-de-greenwashing-destructrice/[15] GRAIN, “Purchasing land in Niger for carbon credits: the new form of greenwashing sweeping Africa”, 9 November 2022, https://grain.org/en/article/6909[16] GRAIN, “From land grabbers to carbon cowboys: a new scramble for community lands takes off”, 25 September 2024, https://grain.org/en/article/7190[17] Arbaud Deux, “La Côte d’Ivoire se lance dans les crédits carbones pour financer sa reforestation” (EN: “Côte d’Ivoire launches carbon credit scheme to finance reforestation”), Le Monde, 1 May 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2024/05/01/la-cote-d-ivoire-se-lance-dans-les-credits-carbone-pour-financer-sa-reforestation_6230985_3212.html[18] Dr. Simbarashe Tatsvarei et al., “Large scale land-based carbon credit trading within African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), prospects and potential institutional arrangements”, https://www.conftool.org/africalandconference2023/index.php?page=browseSessions&form_session=243&presentations=show[19] Figures are as of 31 December 2023. See Socfinaf, “2023 Annual Report”, https://socfin.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2023-Socfinaf-Annual-report.pdf

Original title: “For Africa’s food and beverage sector, the United States consistently has been one of the top sources of greenfield foreign direct investment, 2006-20”; fromMarket Opportunities Expanding for Agricultural Trade and Investment in Africa,U.S. Department of AgricultureWe know that many foreign companies and investment funds are looking to develop their business in Africa once the AfCFTA becomes operational. For example, major groups from the United Arab Emirates whose activities centre on farm production and trade are banking heavily on the African market thanks to the AfCFTA.[9] The UAE is the 4th largest source of foreign investment in Africa after China, Europe and the United States, and is counting on the AfCFTA to bolster their presence.[10] One key detail worth mentioning is that Abu Dhabi is in the process of signing a free trade agreement with Mauritius to facilitate economic access and legal stability for Emirati firms throughout sub-Saharan Africa, where Mauritius will serve as a bridgehead.[11] In July 2024, the Director of DP World announced that he would be working with the Secretariat of the AfCFTA to handle logistics for future intra-African trade.[12] All these projects risk destabilising communities’ control over land and their own local food markets.The same applies for the new “climate” projects currently taking off in Africa.AfCFTA: will the land market fuel the carbon market?The AfCFTA protocol specifically champions climate projects at a time when foreign investments for the production and sale of carbon offsets are gaining ground.[13] Some, like the TotalEnergies project in Congo, are already being fought against due to their impacts on the rights of local communities.[14] Others are less prominent, such as the agreements signed by African Agriculture Inc with two municipalities regarding 2.2 million hectares of land in Niger.[15] A recent investigation by GRAIN revealed that large-scale tree and crop planting projects for carbon credits cover over 9.1 million hectares of land in the global South, 5.2 million hectares of which are in Africa.[16] In Côte d’Ivoire, the French company aDryada is rapidly expanding with state support, privatising nearly 70,000 hectares of land for its carbon offsetting.[17] These projects are transferring control over the land from peasant, forest and fishing communities to (largely foreign) investors. The AfCFTA risks supercharging this process.The risk is very real indeed. A group of researchers who attended the meeting in Addis Ababa stressed that the carbon credit market in Africa serves mainly foreign interests, the same interests that manage the projects and pocket the revenue. They also emphasised the need to solve the problem of collective land rights for local communities in Africa before these investments are made.[18]Other multinationals that have invested massively in Africa have a different perspective. For example, Socfin – which hold concessions covering 320,000 hectares in Africa for the production of rubber and palm oil – appears concerned about the competition that the AfCFTA could unleash in Nigeria.[19] “If we are unable to manage imports as an ECOWAS country, I find it hard to imagine what will happen when 54 countries begin trading together. As far as we are concerned, it will be a disaster,” declared Graham Hefer, CEO of Okomu Oil Palm Company, Socfin’s most profitable subsidiary in Africa.What can be done about it?It is important to be aware that the AfCFTA may pave the way for international firms, as well as certain wealthy countries, to acquire land to the detriment of local communities in Africa. It is true that there is one option in the protocol’s text that could prevent such a situation. On a national level, governments could designate food or agriculture a “critical sector” to which the protocol on investment would not apply. However, given the importance that African governments attach to the role of private investors, it is unrealistic to think that any one of them would exercise this option.Therefore, it is important to raise awareness of this protocol and debate it, particularly with local communities, who risk losing control of their land, their forests and other resources. Too many of the battles currently being fought in Africa against land grabbing and for climate justice risk being jeopardised by investors who are set to profit from the protocol, all the more so as the agribusiness model itself is central to the agricultural vision of the AfCFTA. We need to promote another path towards a more democratic prosperity, one that is based on popular sovereignty and which respects the rights of local communities.[1] Visit the conference website at https://www.uneca.org/eca-events/2023-conference-land-policy-africa for the documents and videos, in English only.[2] Available in English here: https://www.bilaterals.org/IMG/pdf/en_-_afcfta_protocol_on_investment.pdf. The protocol was adopted on 19 February 2023 and will enter into force once it has been ratified by 22 countries. It is therefore currently being ratified on a national level.[3] In the protocol, the recognition of indigenous peoples is entirely dependent on national legislation; indeed. Very few African nations recognise these peoples, let alone their collective land rights. See Article 3.6.[4] Article 35.2.[5] Liberia and Mali are the exceptions. See https://rightsandresources.org/tenure-tracking/[6] Prachi Agarwal et al, “Exploring data on foreign direct investment to support implementation of the AfCFTA Protocol on Investment”, Overseas Development Institute, 9 September 2024, https://odi.org/en/publications/exploring-data-on-foreign-direct-investment-to-support-implementation-of-the-afcfta-protocol-on-investment/[7] Article 1, definition of “Investor”.[8] Michael E. Johnson et al., “Market opportunities expanding for agricultural trade and investment in Africa”, Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, 6 January 2023, https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2023/february/market-opportunities-expanding-for-agricultural-trade-and-investment-in-africa/[9] GRAIN, “From land to logistics: UAE’s growing power in the global food system”, 12 July 2024, https://grain.org/en/article/7170. The Emiratis’ overall interest in the AfCFTA is explained well by Chido Munyati in “A new economic partnership is emerging between Africa and the Gulf states”, World Economic Forum, 28 April 2024: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/04/africa-gcc-gulf-economy-partnership-emerging/[10] Dubai Chamber of Commerce, “AFCFTA could boost Dubai-Africa trade by 10% over next 5 years”, 17 August 2020, https://www.dubaichamber.com/en/media-center/news/afcfta-could-boost-dubai-africa-trade-by-10-over-next-5-years/[11] Emirates News Agency, “AE ministers, officials emphasise importance of Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement with Mauritius”, 22 July 2024 https://www.wam.ae/en/article/b4ag6p1-uae-ministers-officials-emphasise-importance[12] Nehal Gautam, “How will AfCFTA transform intra-African trade & overcome regulatory issues?”, Logistics Update, 13 July 2024, https://www.logupdateafrica.com/trade/how-will-afcfta-transform-intra-african-trade-overcome-regulatory-issues-1352649[13] See Article 26(a) in particular[14] CCFD, “Total au Congo, une opération de greenwashing destructrice” (EN: “Total in Congo: a destructive greenwashing operation”) updated 25.09.2024, https://ccfd-terresolidaire.org/total-au-congo-une-operation-de-greenwashing-destructrice/[15] GRAIN, “Purchasing land in Niger for carbon credits: the new form of greenwashing sweeping Africa”, 9 November 2022, https://grain.org/en/article/6909[16] GRAIN, “From land grabbers to carbon cowboys: a new scramble for community lands takes off”, 25 September 2024, https://grain.org/en/article/7190[17] Arbaud Deux, “La Côte d’Ivoire se lance dans les crédits carbones pour financer sa reforestation” (EN: “Côte d’Ivoire launches carbon credit scheme to finance reforestation”), Le Monde, 1 May 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2024/05/01/la-cote-d-ivoire-se-lance-dans-les-credits-carbone-pour-financer-sa-reforestation_6230985_3212.html[18] Dr. Simbarashe Tatsvarei et al., “Large scale land-based carbon credit trading within African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), prospects and potential institutional arrangements”, https://www.conftool.org/africalandconference2023/index.php?page=browseSessions&form_session=243&presentations=show[19] Figures are as of 31 December 2023. See Socfinaf, “2023 Annual Report”, https://socfin.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2023-Socfinaf-Annual-report.pdf