The grain trade is in trouble again. The United Nations is trying to preserve the international agreement, set to expire May 18, that enables the export of Ukrainian grain from Black Sea ports, but Russia has signaled that it will not agree. Moscow says the almost year-old deal involving the U.N., Russia, Ukraine and Turkey has fallen short of its demands, but its larger motivation is to use the deal as leverage in its economic war with the West. Russia has space to maneuver because it is close to its export quota. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov discussed the grain deal with U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres on Monday, and more meetings will take place in the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, the European Union’s agriculture ministers met on Tuesday to discuss the agrifood situation in the bloc and the war’s impact. This comes after Poland, Hungary, Slovakia and Bulgaria imposed import bans on Ukrainian products last week. (Romania, another country that has seen farmer protests over the influx of Ukrainian products, has stopped short of a ban and is consulting with Ukraine and the EU.) EU officials condemned the import bans and instead proposed additional financial support for farmers as well as steps to ensure that Ukrainian grains moving through the EU make their way out of the bloc.

Appeals for EU Aid

More than 23 million tons of Ukrainian grains have been transited through and sold on the European market since the EU adopted last June a regulation temporarily liberalizing trade with Ukraine. In November, Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia and Hungary notified the European Commission about the issue. Unbound by high EU quality standards, they said, Ukrainian producers and traders were dumping goods in their countries and hurting their farmers.

A large part of the problem is that Ukraine’s non-occupied Black Sea ports have limited capacity, which forces one of the world’s largest grain producers to shift exports to other routes. The largest port in the area, Romania’s Constanta, is busy because of not only Ukrainian grains but also increased traffic from the so-called Middle Corridor through the Caspian and the Caucasus. (Georgia and Romania have both increased cargo traffic capacity, since trade with China can no longer be done through Ukraine.) According to research by Lloyd’s List, a shipping journal, about 70 percent of Ukraine’s displaced trade is flowing through the Port of Constanta, with most of the rest redirected to the Polish ports of Gdynia and Gdansk. The majority of Ukraine’s export volume is being moved by sea, with the rest moving by rail (35 percent) or road (12 percent). Although Ukraine’s infrastructure minister said last year that building up Europe’s rail network was a strategic objective, construction is still underway. If Russia refuses to renew the grain deal next month, the Constanta port and the Danube will become even busier.On March 22, the European Commission proposed using 56 million euros ($61 million) from the EU budget to help Poland, Bulgaria and Romania cope with the increased imports of cereals and oilseeds from neighboring Ukraine. The bulk of the aid, approximately 30 million euros, was earmarked for Poland, with Bulgaria and Romania receiving roughly 17 million euros and 10 million euros, respectively. Dissatisfied with Brussels’ reply, Warsaw unilaterally closed its border to Ukrainian agricultural products on April 15. Others soon followed. Poland reopened its border on April 18, but only for transit; Ukrainian agrifoods are still prohibited from being offloaded inside Poland. Again, others followed suit.

The EU is giving Ukraine funds to modernize production and adopt EU quality standards. By officially associating Ukraine with the EU single market, the EU is restricting Ukraine’s ability to sell grains – or anything else that does not meet high EU standards – within the bloc. The adaptation to the EU market is a lengthy process, requiring not only funding but also skilled human resources, which can be in short supply in wartime. Knowing all this, it is likely that Ukraine’s producers want to sell their grains fast to the closest markets possible, like the ones the goods are transiting through.Effects on Russia

Ironically, Russia finds itself in similar distress as Europe. Grain production and stocks globally were high last year, and the surplus needs to be sold before new crops can reach markets. Russia had a record harvest in 2022, and it is likely nervous about the news that three of the world’s largest grain traders – Cargill, Viterra and Louis Dreyfus Co. – will stop operating in Russia in July. Moscow says local operators will replace them, but their business is not something that can be learned overnight, meaning some Russian grains could go unsold.

Because of the grain glut, Russian farmers, like their European counterparts, are no longer assured a decent profit. The Kremlin wants to ensure that farmers don’t go out of business and threaten social stability (a lower risk than in Europe, but a risk nonetheless). Collapsing profits also diminish the ability of Russian farmers to invest in seeds and other materials for the next crop season, potentially threatening the Russian food supply.

One way Russia may be dealing with this is by covertly blending its grain with Ukrainian production. There is little that Kyiv could do about this; after more than a year of war, Ukraine’s black market has grown. In other words, some of what European farmers believe to be Ukrainian grain could be from Russia. This helps Russian producers profit and exerts even more pressure on frontline EU countries, driving a wedge between them and Brussels. It also opens rifts between Ukraine and Poland, its closest ally.Reconstruction Challenges

Although supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic are ending, the war in Ukraine highlights a new threat for Europe: that Ukraine will become a black hole for business. The war has already changed trade routes. A fifth of Ukraine is under Russian control, and the rest is under Russian attack. The West is discussing the country’s reconstruction, but it will first need to protect itself from the spillover effects stemming from the growth of Ukraine’s black market and of illicit trade, from drugs to human trafficking.

Europe remembers how to deal with post-conflict reconstruction. Its most recent experience with it was in the Western Balkans. But although more than three decades have passed since those wars, the area is still receiving EU funding and in many ways is still under reconstruction. In Ukraine, the rebuilding process will have to contend with Russia’s growing influence.

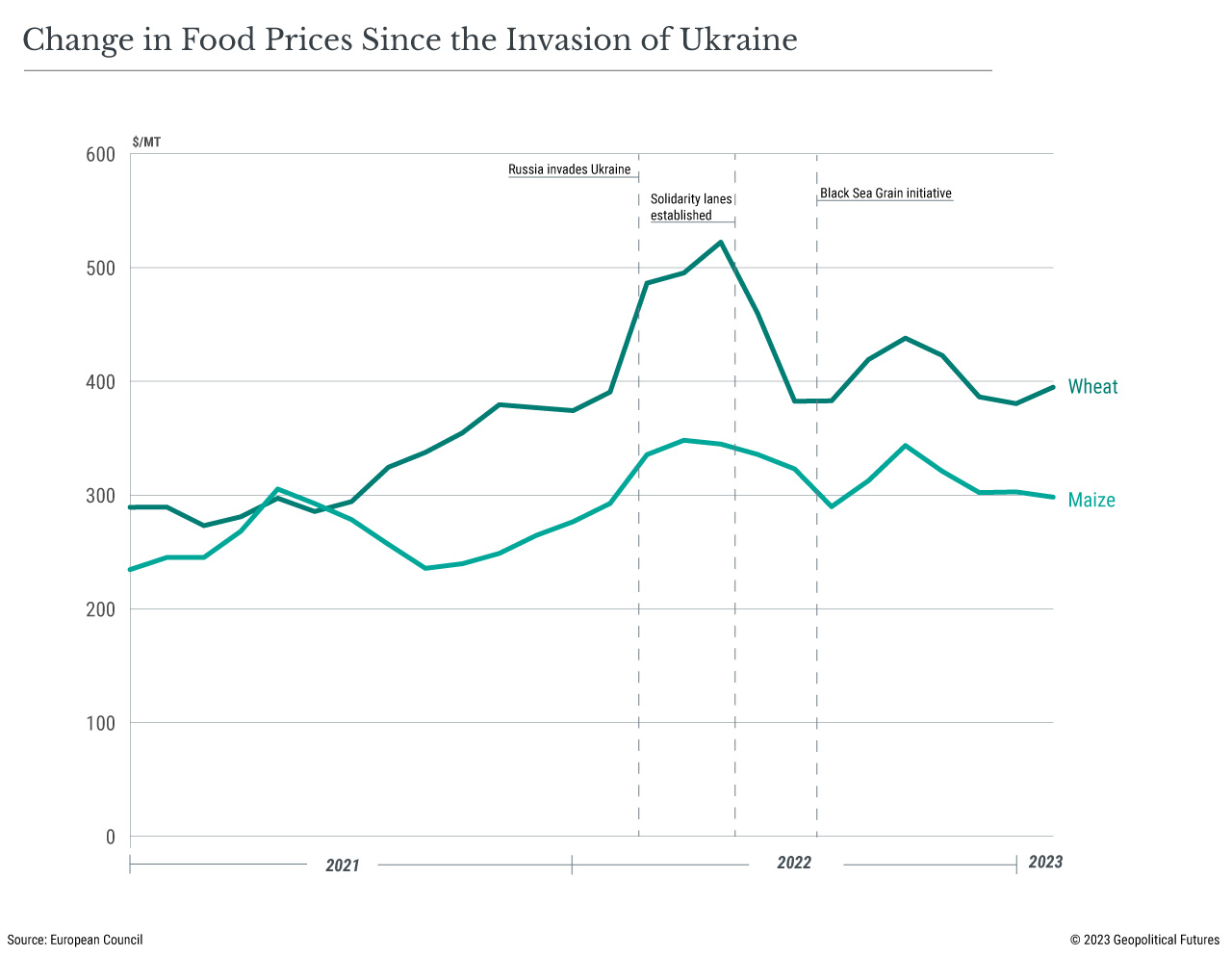

Grain transit is just one in a series of problems to come for Europe and Ukraine. The Ukrainian economy will continue to be transformed by the war and the competition for influence between Russia and the West. Though grain prices are down significantly from recent highs, their direction in the coming months will be determined by events in the Black Sea region, including the fate of the grain deal.